As a naval architect, I find the Coriolis project particularly exciting—not just because it’s another hydrogen vessel joining the fleet, but because it’s a floating laboratory specifically designed to advance the very technologies it uses. The fact that Hereon chose to develop and test their own metal hydride storage system on this vessel, rather than relying on conventional compressed or liquid hydrogen solutions, demonstrates the kind of bold experimentation the industry needs right now.

Germany’s Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon has officially taken delivery of the research vessel Coriolis, marking a significant milestone in both marine hydrogen technology and coastal research. Christened on November 18, 2024, at the Hitzler Werft shipyard in Lauenburg, the 29.9-meter vessel represents a globally unique approach to maritime hydrogen propulsion—using metal hydride storage technology developed in-house by Hereon’s Institute of Hydrogen Technology.

The €18 million vessel, funded primarily by the German Federal Government, was delivered in January 2025 and is now operational for research missions in the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and shallow coastal waters.

What sets Coriolis apart is its dual purpose: it’s simultaneously a coastal research platform and an innovation testbed for hydrogen maritime technologies, specifically designed to validate the metal hydride storage system developed by Hereon. Named after French scientist Gaspard Gustave de Coriolis (1792-1843), the vessel entered service in early 2025.

Vessel Specifications

Key Technical Data:

- Length Overall: 29.9 meters (98.1 feet)

- Beam: 8.0 meters (26 feet)

- Draught: 1.6 meters (5.2 feet)—shallow enough for Wadden Sea operations

- Maximum Speed: 12 knots

- Range: 100 nautical miles

- Crew: 2 (+1 optional)

- Scientists: Up to 12

- Operating Days/Year: 225

- Laboratory Space: 47 m²

- Working Deck: 70 m² with stern A-frame

- Total Engine Power: 750 kW

Innovative Propulsion System

The Coriolis employs a hybrid diesel-electric, battery-electric, and hydrogen-electric propulsion concept. Electric traction motors drive the vessel’s two propellers and can draw power from three different sources:

- 100 kW Hydrogen Fuel Cell: Supplied by hydrogen from the metal hydride storage system

- Battery Bank: For short-term, high-power demands

- 45 kW Diesel Generator: Backup power for extended missions

Hydrogen Operation Duration: Approximately 5 hours on a single tank charge in pure hydrogen mode.

The Metal Hydride Storage Breakthrough

What Makes Metal Hydride Storage Different?

The Coriolis is the first commercial research vessel to use metal hydride (MH) hydrogen storage instead of conventional compressed (350-700 bar) or liquid hydrogen (-253°C) systems. This technology, previously used in German U212 and U214 class submarines, offers several distinct advantages for maritime applications:

Storage Capacity:

- Metal Hydride Tank System: 5 tonnes total weight

- Hydrogen Capacity: 30 kg of hydrogen

- Volumetric Density: >50 g H₂/liter at system level

- Operating Pressure: <60 bar (vs. 350-700 bar for compressed hydrogen)

- Operating Temperature: -30°C to +50°C (vs. -253°C for liquid hydrogen)

Safety Advantages:

- Chemical bonding prevents sudden release of hydrogen in case of valve failure or pressure vessel rupture

- Only 5-10% residual hydrogen could be released abruptly due to porosity

- Much safer than high-pressure or cryogenic storage in marine environments

Design Flexibility:

- Metal hydride tanks can be shaped to fit ship structure

- Can replace ballast water, improving space utilization and stability

- Modular cascade system allows for redundancy and scalability

The Challenge

Metal hydride formation generates heat that must be managed through cooling systems. The vessel uses waste heat recovery to improve overall energy efficiency of the hydrogen system.

Key Partners and Technology Providers

- Owner/Operator: Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon, Institute of Surface Science

- Shipyard: Hitzler Werft, Lauenburg, Germany (construction: January 2023 – January 2025)

- Design Office: TECHNOLOG Services GmbH, Hamburg

- Metal Hydride System: Developed in-house by Hereon’s Institute of Hydrogen Technology

- Fuel Cell: 100 kW PEM fuel cell

- Total Project Cost: €18 million (German Federal Government funding)

The vessel was christened on November 18, 2024, by Karin Prien, Schleswig-Holstein’s Minister of Science, before approximately 400 guests from politics, science, and industry.

Industry Context: Research Vessels Leading Hydrogen Adoption

Research vessels are proving to be ideal platforms for hydrogen technology development:

Similar Hydrogen Research Vessels:

- Energy Observer (France): Liquid hydrogen-powered catamaran

- Hydra (Norway): Liquid hydrogen ferry with LOHC testing capability

- H₂ Barge 1 (Netherlands): Inland hydrogen bunker and supply vessel

The research vessel segment benefits from:

- Controlled operational profiles with known routes and durations

- On-board scientific teams capable of monitoring and optimizing systems

- Strong government funding for technology demonstration

- Lower commercial pressure allowing for innovation testing

The Coriolis takes this concept further by making hydrogen technology itself a primary research subject, not just a propulsion solution.

Connection to H2Mare Flagship Project

The Coriolis directly supports Germany’s H2Mare hydrogen flagship project, one of three major initiatives funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) with up to €740 million total allocation. H2Mare focuses on producing green hydrogen and derivative products using offshore wind power.

Hereon contributes to H2Mare through four of its institutes, advancing:

- Offshore hydrogen production technologies

- Hydrogen storage and transport solutions

- Membrane-based gas separation and purification

- System integration for maritime applications

Operational Challenges and Considerations

While the Coriolis represents technological advancement, several practical challenges remain:

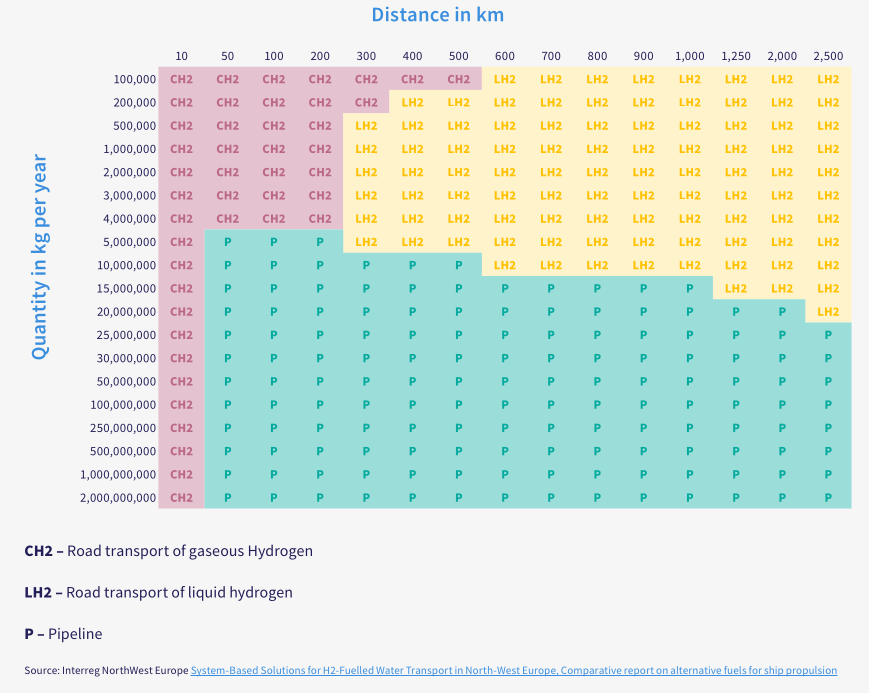

Hydrogen Infrastructure:

⚠️ BOTTLENECK: Germany currently has limited hydrogen bunkering infrastructure for vessels. The Coriolis will need to coordinate with specialized facilities or use mobile refueling solutions.

Operational Range:

- 5 hours of pure hydrogen operation limits extended offshore missions

- 100 nautical mile total range requires careful mission planning

- Diesel backup essential for current operations until hydrogen supply chain matures

Refueling Logistics:

- Metal hydride refueling requires cooling capacity during hydrogen loading

- Refueling time longer than conventional fueling but safer than liquid hydrogen

- Specialized training needed for crew and port personnel

Technology Validation Period:

As this is the world’s first commercial application of metal hydride storage in a research vessel, 2025 will be a critical year for validating:

- System reliability in varied sea conditions

- Practical refueling procedures

- Heat management during extended operations

- Overall operational economics

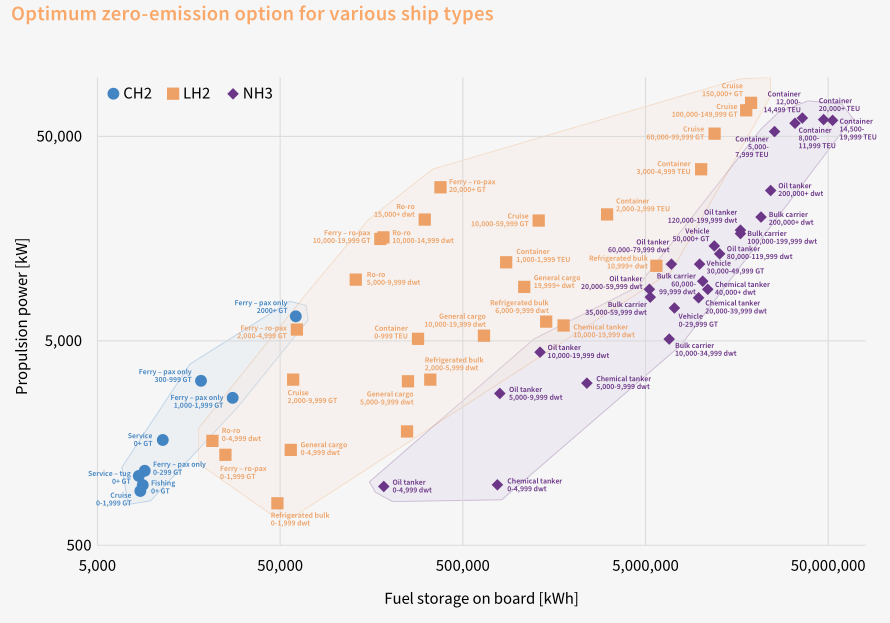

Why Metal Hydrides Matter for Maritime Hydrogen

The Coriolis demonstrates a storage solution that could be particularly attractive for smaller vessels and harbor craft:

Advantages for Maritime Applications:

- Safety: Lower pressure and ambient temperature reduce explosion risk

- Structural Integration: Flexible tank shapes can optimize ship design

- Stability: Dense storage low in hull improves metacentric height

- Ballast Replacement: Hydrogen storage serves dual purpose

- No Boil-Off: Unlike liquid hydrogen, no fuel is lost during storage

Current Limitations:

- Weight Penalty: 5 tonnes of tank system for only 30 kg hydrogen (167:1 ratio)

- Energy Density: Still lower than diesel on a total system basis

- Cooling Requirements: Heat management adds complexity

- Cost: Specialized metal alloys and tank fabrication increase expenses

- Refueling Speed: Slower than compressed hydrogen due to thermal constraints

However, for vessels with predictable routes, shore-based power access, and weight tolerance, metal hydrides offer compelling safety and design advantages that could make them the preferred solution for certain applications.

Looking Ahead: Metal Hydride Hydrogen as a Maritime Solution

As the Coriolis begins operations in 2025, the maritime hydrogen industry will be watching closely. Key questions to be answered:

- Can metal hydride storage achieve the reliability needed for commercial maritime service?

- Will the safety and design advantages offset the weight penalty and refueling complexity?

- Can the technology scale up for larger vessels or be optimized for specific niches like harbor tugs, ferries, and coastal workboats?

- What refueling infrastructure investments will be required to support metal hydride vessels?

Real-time operational data from Coriolis—available via the public dashboard—will provide invaluable insights for the broader maritime hydrogen transition. Every operational hour, every refueling cycle, every equipment performance metric becomes a data point that advances our collective understanding of metal hydride storage at sea. This is exactly the kind of real-world validation the hydrogen shipping sector needs to move from concept to commercial deployment.

Conclusion: A Critical Test Platform for Maritime Hydrogen

The €18 million investment in the Coriolis represents more than just a new research vessel for Germany—it’s a commitment to developing practical, safe hydrogen technologies specifically optimized for maritime environments. By making the vessel itself an experimental platform for metal hydride storage, Hereon has created a powerful feedback loop between hydrogen research and real-world maritime application.

As Prof. Regine Willumeit-Römer, Scientific Director at Hereon, stated during the christening: “CORIOLIS will become our brand ambassador by researching complex systems… It is not only fundamental for coastal research, but also a tool for our entire center, because hydrogen and membrane technology are also used on board.”

The vessel is expected to operate approximately 225 days per year, ensuring extensive operational data collection for metal hydride hydrogen storage validation. With Germany’s ambitious hydrogen strategy and the expansion of offshore wind capacity in the North and Baltic Seas, the Coriolis arrives at exactly the right moment to help demonstrate whether metal hydride storage can be a practical solution for the maritime sector’s transition to zero-emission operations.

Sources

- Baird Maritime: “VESSEL REVIEW | Coriolis – Hybrid hydrogen-powered research vessel delivered to German science institute” (January 21, 2026)

- Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon official website: Research Vessel Coriolis project pages

- Innovations Report: “Hereon Unveils New Ship CORIOLIS in Grand Naming Ceremony” (November 20, 2024)

- Power-to-X.de: “Research vessel Coriolis to embark on missions in 2025” (December 16, 2024)

- NOW GmbH: “Onboard power for the CORIOLIS” (January 25, 2024)

- German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) H2Mare project information